- Early on, Canada-based The Metals Company cast the rocks it seeks to mine from the deep seafloor as a crucial resource for electric vehicle batteries and other green technologies, positioning them as a solution to the accelerating climate crisis.

- However, in 2024, another message overtook the first in TMCs communications, according to an analysis by Mongabay and collaborators. It now cast these same rocks as strategic assets, essential for strengthening the mineral dominance and national security of the U.S., where the company has a subsidiary.

- This narrative pivot seems to have helped TMC position itself to act on potential U.S. approval for deep-sea mining even before the Trump administration gave its formal authorization in April, and may well provide the momentum needed to launch this contentious and still highly speculative industry.

- TMC did not address the specific claims Mongabay presented in this investigation regarding the companys narrative strategies. Instead, in a statement, TMC criticized Mongabay for being increasingly captured by activist narratives, while offering no comment on its own messaging aimed at investors and the public.

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Centers Ocean Reporting Network, where Elizabeth Claire Alberts is a fellow. It is part two of an investigation into TMC, its investors, partners and business strategies. Read part one here .

There are at least two versions of the pitch. One casts polymetallic nodules metal-rich rocks scattered across flat stretches of the deep seafloor as a crucial resource for electric vehicle batteries and other green technologies, positioning them as a solution to the accelerating climate crisis. The other frames these same nodules as strategic assets, essential for strengthening U.S. mineral dominance and enhancing national security. There is also a version of the pitch that mixes these two possibilities, presenting nodules as a critical material poised to both save the planet and secure it at the same time.

The company promoting these messages is Canada-based The Metals Company (TMC), a firm aiming to mine the deep sea and the companys charismatic and media-savvy CEO, Gerard Barron is the one usually delivering them. Barron, who used to work in sales, often speaks with image-rich, even metaphorical language. For instance, in media interviews, Barron has dubbed nodules as a battery in a rock, and also compared them to golf balls on a driving range that can easily be scooped up by machinery that would only disturb the top 5 centimeters (2 inches) of the seafloor roughly the length of two bottle caps laid end to end.

Early on, starting a little before TMC went public in 2021, listing on the Nasdaq exchange in New York, Barron focused heavily on the first narrative, about harvesting nodules as a planet-saving necessity. But over time and amid accusations from scientists and NGOs that the industry could, in reality, irreversibly damage the marine environment Barron, and by extension TMC, began to shift this message. The company didnt entirely drop its eco-conscious argument, but it began placing greater emphasis on the concept that seabed resources were essential to U.S. national security. As Barron wrote in a letter published in The Economist on June 26, 2025, deep-sea minerals are not only essential to clean energy, but are foundational to national defence, supply-chain security and industrial resilience.

TMC has used this national security rationale for its mission to cultivate support in Washington, D.C., as evidenced in the lobbying disclosures filed by firms working on the companys behalf. These disclosures indicate the lobbying efforts focused not only on national security in broad terms, but also on specific legislation such as the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2025 and the Critical Minerals Security Act. The emphasis on national security seems to have helped TMC position itself to act on potential U.S. approval for deep-sea mining even before the Trump administration gave its formal authorization in April. Other deep-sea mining companies like Impossible Metals and American Metal espouse this rationale as well. TMCs narrative pivot toward U.S. national security has aligned with the current political climate, and may well provide the momentum needed to launch this contentious and still highly speculative industry that some scientists say could trigger a new wave of harm on ocean ecosystems.

TMC did not address the specific claims Mongabay presented in this investigation regarding the companys narrative strategies. Instead, in a statement, TMC criticized Mongabay for being increasingly captured by activist narratives, while offering no comment on its own messaging aimed at investors and the public.

Read TMCs full statement here.

This is the second part of an investigation into TMC, its investors, partners and business strategies, conducted by Mongabay with support from the Pulitzer Center.

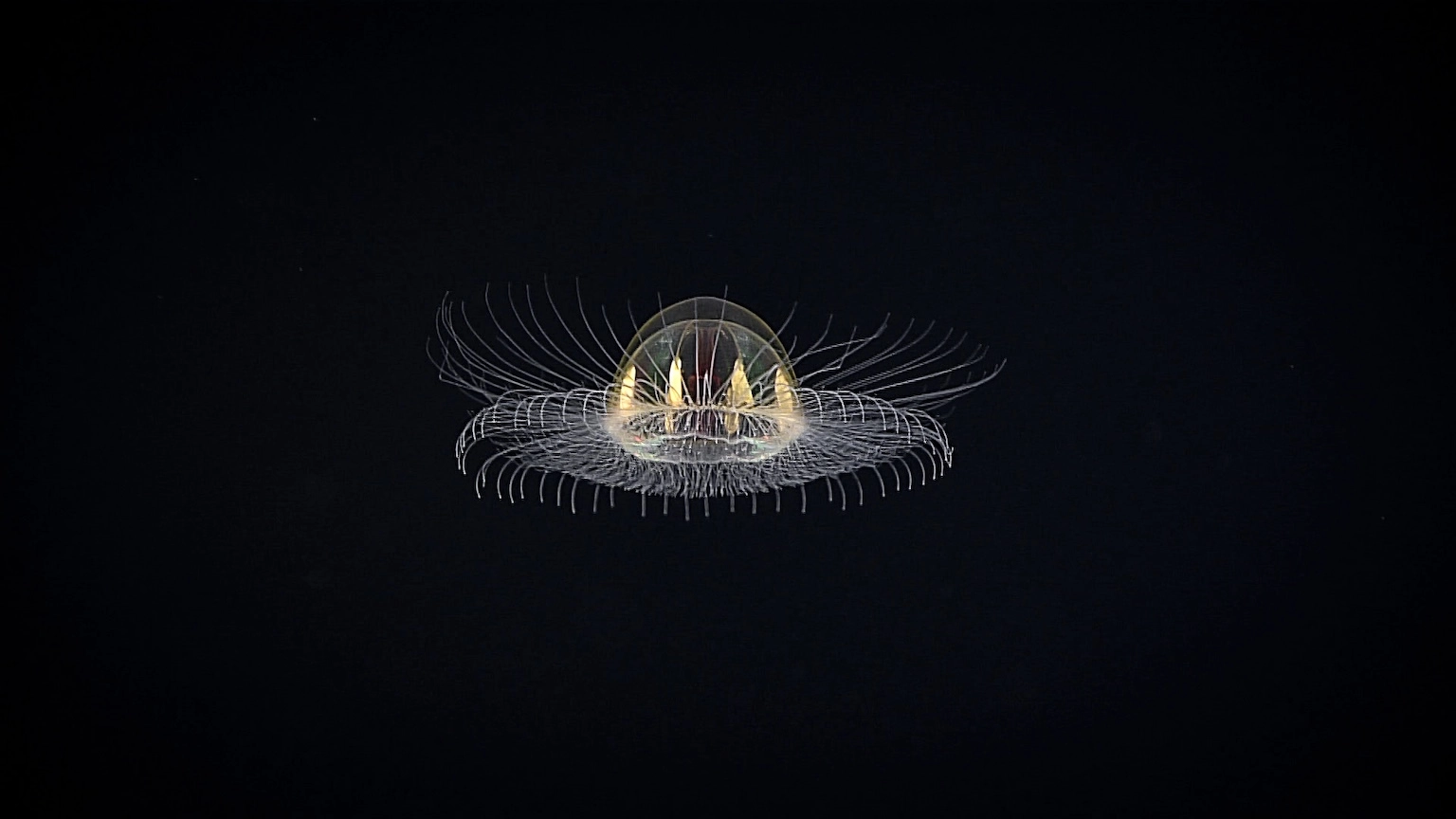

A deep-sea jellyfish (genus Atolla) photographed at a depth of at least 1,500 meters (4,920 feet) in the western Pacific Ocean. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0).

A deep-sea jellyfish (genus Atolla) photographed at a depth of at least 1,500 meters (4,920 feet) in the western Pacific Ocean. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0). In the years leading up to its 2021 Nasdaq debut, TMC promoted an image of itself as a pioneer of a cleaner, more sustainable form of mining. Not only could it harvest critical minerals without causing substantial harm to the marine environment, the company argued, but these very minerals which are abundant in a stretch of seabed in the Pacific Ocean known as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) could be used to make batteries for electric vehicles, solar panels and other green technologies, fueling the energy transition needed to fight climate change.

Back in 2018, when the company went by the name DeepGreen Metals, it released a cinematic video that framed deep-sea mining as a novel solution to the planets most trying environmental challenges. In the short film, Barron strolls along a picturesque seaside cliff as he describes DeepGreens quest for a more sustainable planet, and argues that seabed minerals and specifically DeepGreen itself are essential to achieving that vision. Also featured in the video is Gregory Stone, formerly the chief scientist of the U.S.-based NGO Conservation International, who became TMCs chief ocean scientist that year. Against the backdrop of breaking waves, Stone frames deepsea mining as an urgent necessity: Humans have now occupied every corner of the planet, and weve come to a point where we have to find a way for us to continue to exist on this planet. The solution, he suggests, is to mine the deep seabed. (The company has since taken the video offline but it is still viewable in a Los Angeles Times article.)

In another video published in March 2020, Barron described how he would explain the need for deep-sea mining to kindergarteners: Mother Nature knew that to move away from all those nasty fossil fuels that created much of the climate crisis thats in front of us, that were going to need a heap of metals & But Mother Nature had a little secret, and the secret was waiting for us on the seafloor.

A preliminary analysis of the content of more than 130 of TMCs press releases published over a six-year period, conducted by marine social ecologist Ellycia Harrould-Kolieb of the University of Melbourne in Australia, Mongabay and the Pulitzer Center, found that the company predominantly used language that painted an image of deep-sea mining as a sustainable and necessary industry, and of TMC as a company with high standards committed to lowering environmental harm.

The analysis found that there was a steady rise of this green framing between 2019 and 2020, followed by a sharp increase from 2020 to 2021. When deploying this green framing, TMC frequently used terms such as sustainable, ESG, clean energy, biodiversity and lower impact in its press releases aimed at investors, stakeholders and the broader public. However, the use of this green framing began to wane in 2021 and sharply deceased in 2023. Terminology around the national security benefits of deep-sea mining, including defense, military, security, United States and China, steadily rose beginning in 2022, until it became the primary framing used in TMCs press releases in 2024. Read the methodology of the text analysis here.

While the company was emphasizing its green transition argument, it released studies to substantiate its claims. In 2020, it released a white paper arguing that deepsea mining offered a strong path to securing critical minerals while minimizing the impacts associated with landbased mining. It was presented as an independent inquiry but had four TMC employees, including Stone, and one TMC consultant listed as the coauthors. That same year, many of these arguments were reiterated in a peerreviewed article in the Journal of Cleaner Production . This was also presented as an independent inquiry, yet featured Erika Ilves, Barrons reported life partner who has served as TMCs chief strategy officer since 2018, as a contributor. Several years later, in 2023, London-based reporting agency and information provider Benchmark Mineral Intelligence published a TMC-commissioned life cycle assessment that concluded that extracting seabed minerals would have a lower environmental impact than landbased mining in nearly all categories studied. Olivia Lin, a senior sustainability analyst at Benchmark who worked on the assessment, told Mongabay that TMC supplied much of the primary data for the review. TMC declined to comment on these findings. In other contexts, however, TMC has promoted peer-reviewed research that appears to have been prepared independently.

As TMC promoted this green-focused narrative, skepticism and backlash were growing among scientists and marine conservation organizations. In 2019, the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition (DSCC), a Netherlands-based coalition of more than 100 organizations promoting deep-sea protection including Greenpeace, Oceana, and Stones former organization, Conservation International began campaigning for a moratorium against deep-sea mining. By early 2021, WWF, a DSCC member, had facilitated pledges from several major brands, including BMW Group, Volvo Group and Google, to refrain from using deep-sea minerals in their supply chains. In 2022, the Pacific island nation of Palau became the first country to officially call for a moratorium on the industry, followed closely by numerous other countries, including Chile, Spain and France.

Initially, TMC expressed alignment with the concerns of NGOs and industry. For instance, in March 2021, the company released an open letter stating that it agreed with WWF and these brands about seafloor mineral development needing to be approached cautiously and with an exacting commitment to science-based impact analysis and environmental protection. But over time, that alignment frayed. By April 2025, when TMC announced its decision to apply for mining rights via the U.S. rather than the International Seabed Authority (ISA), the U.N.-associated regulator that oversees deep-sea mining in international waters, Barron was openly criticizing NGOs and nations calling for a moratorium. In a March statement, he accused them of treating the deep sea as their last green trophy while leaving the aspirations and rights of developing states that sponsored private companies like TMC as roadkill.

Meanwhile, TMCs stock price slid. Nasdaq issued the company at least four delisting notices between December 2022 and January 2025 after its share price remained below the $1 mark for more than 30 days. At the same time, the company was grappling with prolonged regulatory delays from the ISA, through which TMC had initially hoped to secure its mining license. In its financial disclosures, TMC acknowledged that these delays could have an adverse impact on its business. TMC did not comment on this matter in its response to Mongabay.

Read part one of Mongabays investigation into TMC, its investors, partners and business strategies here.

Read part one of Mongabays investigation into TMC, its investors, partners and business strategies here. TMC referenced U.S. national security themes as early as 2021, but it wasnt until 2023 amid a prolonged slump in its stock price and stalled negotiations at the ISA that the Canadian firm significantly recalibrated its messaging. While it continued to highlight the environmental advantages of deep-sea mining, TMC increasingly shifted its messaging to emphasize its potential role in supplying critical minerals for U.S. national security and defense. According to the analysis by Harrould-Kolieb, Mongabay and the Pulitzer Center, the company began reducing its use of green framing terms like sustainable and clean energy in its press releases and more frequently using terms like United States, Congress, China and defense. In late 2023, this national security-oriented language overtook its use of environment-themed terminology.

Also beginning around the time TMC went public, the company has been quietly building its influence in Washington, D.C., emphasizing the new national security narrative. Around July 2021, TMC enlisted the services of Bracewell, a Houston-headquartered lobbying firm with a focus on representing oil and gas companies. Lobbying records indicate that TMC paid the firm $570,000 over the next three years to lobby the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. Bracewell did not respond to Mongabays request for comment.

In 2023, TMC also brought on the Vogel Group, a Washington, D.C.-based lobbying firm that has represented some controversial clients, including the NSO Group, an Israeli spyware company the U.S. blacklisted for national security reasons. The Vogel Group has strong ties to U.S. lawmakers. For example, one of its lobbyists working on TMCs behalf is Shaun Taylor, a former deputy chief of staff to Texas Representative Pat Fallon, who has expressed support for deep-sea mining. In December 2023, while Taylor was working for Fallon, Fallon co-signed a letter urging then-Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin to develop a plan to address the national security ramifications of the Chinese Communist Partys (CCP) interest and investment in seabed mining a development that TMC loudly promoted. Vogel did not comment on these findings.

While TMC stopped working with Bracewell in 2025, it continued working with the Vogel Group, paying the company $500,000 over more than two years for its services. Over the course of their working relationship, records indicate that the Vogel Group has lobbied multiple government agencies on behalf of TMC to position seabed mining as a source of critical minerals and a national security asset. Samir Kapadia, the Vogel Groups managing principal and TMCs main lobbyist, confirmed these lobbying aims with Mongabay. Since Ive worked with the company, the focus has always been around national security and minerals independence, he said.

Deep-sea mining had begun to gain traction in the U.S. during the administration of President Joe Biden, tied firmly to national security interests and spurred on by a series of public endorsements and legislative pushes from prominent politicians many of which TMC promoted through press releases and social media. For instance, the 2024 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which Biden signed into law in December 2023, called for increased research into securing polymetallic nodules and assessing U.S. capabilities to mine and process them. The 2025 NDAA, which Biden signed into law in December 2024, went a little further. It authorized a study by the assistant secretary of defense for industrial base policy to assess the feasibility of improving domestic capabilities for refining polymetallic nodule derived intermediates into high purity nickel, cobalt sulfate, and copper for defense applications.

Deep-sea mining has gained support from numerous prominent politicians. Among them is the current secretary of state, Marco Rubio, who previously appealed (unsuccessfully) to the U.S. Development Finance Corporation to support the deep-sea mining sector in the Pacific nation of Cook Islands. Other prominent supporters of deep-sea mining have included U.S. representatives Elise Stefanik of New York and Rob Wittman of Virginia, who have signed letters urging the Department of Defense to see deep-sea mining as a pathway to securing the nations critical mineral supply and countering Chinas influence in the sector, and the current secretary of commerce, Howard Lutnick, who endorsed deep-sea mining at his Senate confirmation hearing in January 2025, having previously served as the chief executive of Cantor Fitzgerald, a firm that has financially advised TMC.

The deep-sea mining industry has also gained support from influential Washington, D.C.-based organizations and think tanks. Among them are the Wilson Center, which published a report in 2024 arguing that seabed mining could bolster U.S. supply chain resilience, and SAFE (Securing Americas Future Energy), a nonpartisan group that has actively promoted the industry. SAFEs CEO, Robbie Diamond, is listed as a director of at least two deep-sea mining companies: CIC Limited, a Cook Islands-based firm with U.S. ties seeking to mine within the Cook Islands exclusive economic zone, and Glomar Minerals, a new U.K.-based company. Leslie Hayward, the senior vice president of public affairs at SAFE, told Mongabay that Diamond became interested in polymetallic nodules after SAFE began promoting deep-sea mining in 2020, and that he recued himself from SAFEs work on this issue in 2022.

While deep-sea mining appeared to gain traction in Washington, D.C., under the Biden administration, TMC still had no clear pathway to obtain a mining license. Then, things changed for TMC when Donald Trump won back the presidency. After Trumps inauguration on Jan. 20, Barron wrote an enthusiastic post on LinkedIn, accompanied by a photo of himself at the Nasdaq desk holding a polymetallic nodule to the camera. Congratulations to President Donald Trump on his inauguration, which heralds a new dawn for U.S. energy and industry, Barron wrote. With a day one pledge to bring new sources of minerals online and on time, we stand ready to help deliver U.S. mineral independence and get America rockin again.

TMC was indeed standing ready. On Jan. 29, barely a week after Trump took office, the company applied to change the name of its U.S. subsidiary from DeepGreen Resources to The Metals Company USA, according to records obtained by Mongabay. This rebranding of a subsidiary established in 2013 aligned with Trumps America First policy. In the coming weeks, the company used TMC USA to apply for mining rights under a 1980 U.S. law called the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act (DSHMRA), which was designed as an interim measure to give the U.S. a domestic legal framework to authorize seabed mining in international waters until an acceptable global agreement was reached, according to the U.S. Ocean Commission. TMC had to apply through its U.S. subsidiary in order to comply with DSHMRA, which limits the U.S. to granting such rights exclusively to U.S. citizens and corporations.

Then, on April 24, three months after Trump assumed office, the White House issued its executive order aiming to launch the deep-sea mining industry. It declared that the U.S. has a core national security and economic interest in maintaining leadership in deep sea science and technology and seabed mineral resources, and that developing the deep-sea mineral sector would ensure secure supply chains for our defense, infrastructure, and energy sectors while countering Chinas influence over the seabed mineral sector. The order also called for U.S. agencies to expedite permitting of deep-sea mining activities in waters both within and beyond U.S. jurisdiction, collaboration with partners and allies seeking to develop seabed mineral sectors in their own regions, and support for domestic processing facilities. In essence, it aligned closely with TMCs ambitions, not to mention the arguments it had been making for seabed mining for several years - and set the stage for their potential realization.

Kapadia of the Vogel Group, TMCs main lobbyist, told Mongabay that Vogel had been aware that the Trump administration was considering executive action on deep-sea mining early this year and worked to inform government officials about what this order could do for jobs and readiness in the United States. Kapadia said Vogel played no role in drafting the executive order and had no influence on its release, although the executive order is listed under specific lobbying issues on Vogels last two lobbying reports, for the first and second quarters of this year.

A deep-sea lizardfish (genus Bathysaurus) photographed during exploration of Debussy Seamount in the Pacifics Musicians Seamounts in 2017. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0).

A deep-sea lizardfish (genus Bathysaurus) photographed during exploration of Debussy Seamount in the Pacifics Musicians Seamounts in 2017. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0). National security is a broad and ever-evolving concept. It goes beyond traditional notions of military defense, and can refer to a nations economic resilience, technological competitiveness, and energy security. Still, it maintains a militaristic rationale and strong ties to defense infrastructure.

Deep-sea mining, while primarily framed as both a resource and solution to supply chain issues, has intersected with national security interests in surprising ways. For example, in the 1970s, the U.S. government built an apparent deep-sea mining production support vessel, the Hughes Glomar Explorer but instead of being used for mining, the ship took part in a covert CIA mission to recover a sunken Soviet submarine. Now the Glomar name is making a comeback as the newly formed U.K. company, which has applied for exploration licenses in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone that once were owned by a subsidiary of U.S. defense contractor Lockheed Martin.

In addition to those former CCZ licenses, issued by the ISA, Lockheed Martin has held DSHMRA licenses from the U.S. in another part of the CCZ for more than 40 years. Lockheed is now in talks with other companies about providing them access to the minerals in their license areas, according to the Financial Times . Defense-oriented companies have also been key investors in deep-sea mining ventures. Norwegian weaponry company Kongsberg was a primary investor in Loke Marine Minerals, a recently bankrupt Norwegian deep-sea mining company whose executives founded Glomar. And Delaware-registered DYNE Asset Management, a U.S. national-security focused venture capital firm, reportedly invested $40 million in CIC Ltd., the Cook Islands-based deep-sea mining company. DYNE did not respond to Mongabays request for comment.

Yet, according to Arlo Hemphill, the lead for Greenpeaces campaign against deep-sea mining, the overlap between deep-sea mining and defense isnt driven by genuine supply needs, as Trumps executive order implies.

There are no real defense needs for these [seabed] minerals, Hemphill, who is the editor of a recent Greenpeace report on deep-sea minings connections to military, defense and venture capital interests, told Mongabay. All of this was to play on a fear thats already in Washington [about] competition with China. Thats a constant drum beat that you hear from the defense hawks, particularly from the GOP side, and The Metals Company inserted themselves in that conversation.

Hemphill said he believes TMC seized onto this national security narrative after its previous messaging about deep-sea minerals being essential for the green energy transition completely backfired on them. According to Hemphill, this setback was due the emergence of science that showed deep-sea mining would harm ocean ecosystems, regardless of operational safeguards put into place, which led to backlash from environmental organizations and corporations.

In TMCs response to Mongabay, the company stated that we stand firmly behind our record of transparency, science-based decision-making and responsible project development, and also referred to collaboration with world-leading scientific institutions like MIT, Scripps, the UKs NOC and CSIRO, but without citing any specific studies or data sets.

Oliver Lilford, a researcher at the University of Hawaii at Mnoa who investigates the politics of deep-sea mining, said he also sees TMCs references to national security as a deliberate part of its strategy.

Theyve always positioned themselves as being this kind of transformative force for good, and they can use that in different ways, Lilford told Mongabay. For example, he said TMC sought to frame itself this way by arguing that deep-sea mining could lessen the social and environmental impacts associated with terrestrial mining. And more recently, he said, it did so by claiming it could help ease supply chain security concerns, particularly for the U.S. and its Western allies.

A jellyfish (family Rhopalonematidae) photographed around 3,000 meters (9,800 feet) depth at the Utu seamount in American Samoa in 2017. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0).

A jellyfish (family Rhopalonematidae) photographed around 3,000 meters (9,800 feet) depth at the Utu seamount in American Samoa in 2017. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0). Other companies are also promoting the national security argument, adopting strategies similar to TMCs while capitalizing on recent developments in Washington, D.C.

Take Impossible Metals, a deep-sea mining company with plans to raise $1 billion for its proposed operations to mine nodules in the Pacific Ocean, on the boundary of the Cook Islands EEZ. The company has long made the same environmental arguments as TMC about deep-sea mining offering a better alternative to land-based mining while delivering minerals that are critical for electric car batteries and other green technologies. In some ways, it goes a step further, attempting to differentiate itself from other deep-sea mining companies by saying its mining technology, which uses robotics and AI, would cause minimal harm to the marine environment. Then, in November 2023, Impossible Metals submitted a draft unsolicited request to explore U.S. territorial waters around American Samoa for mineral deposits. In its draft request, marked confidential and obtained by Mongabay through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) process, the company urged the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) the federal agency responsible for seabed mineral resources within the boundaries of the U.S. Outer Continental Shelf to consider the request in light of national security requirements for a reliable supplies [sic] of critical minerals.

The companys second unsolicited request, submitted on April 8, 2025, and also obtained by Mongabay through the FOIA process, placed even greater emphasis on U.S. national security. It claimed that Impossible Metals could help secure a critical, Made-in-America supply of the minerals we need for our energy security establishing American leadership in a globally competitive and economically vital space where our adversaries are investing heavily, and provide our military and manufacturers with the lowest cost resource with the lowest environmental impact of any mine in the world. The document stated that by establishing an exploration permitting process, the U.S. can set the standards for seabed mining and capture the economic and security benefits rather than cede this ground to U.S.-hostile UN organizations eager to expand their authority.

Oliver Gunasekara, Impossible Metals CEO, told Mongabay in an email that the company had been using all the arguments for a long time.

There is no energy transition, no vital infrastructure, no digital transformation, and no defensive resilience without critical metals, Gunasekara said. One component does not replace another. National security and energy transition are both equally important.

Another newcomer drawing on the national security narrative is American Metal, a deep-sea mining firm incorporated in Texas on Feb. 18, 2025. This company is led by David Heydon, an industry veteran who helped found several deep-sea mining companies, including the former Nautilus Minerals; TMCs precursor, DeepGreen; and TMC subsidiary Nauru Ocean Resources Inc. (NORI). Now, Heydon and his son, Robert, have teamed up at American Metal. The companys website, which it registered on Jan. 21, 2025 just one day after Trump returned to office features language about securing critical minerals exclusively for the United States that will advance national security, economic resilience, and industrial self-reliance.

While it is uncertain if American Metal has applied for a mining permit, a preliminary response from NOAA to a FOIA request Mongabay filed in April confirmed that company representatives had contacted the agency earlier this year. NOAA declined to comment on its communications while this FOIA request is pending. American Metal also did not respond to Mongabays request for comment.

Other deep-sea mining companies appear to be positioning themselves to take advantage of the new era ushered in by Trumps executive order. While they havent necessarily aligned themselves with the national security rationale for the industry, Mongabay has found through the FOIA process that numerous U.S. companies, including Wetstone, Odyssey Marine Exploration, and Transocean, have engaged with BOEM about the possibilities enabled by the order.

Polymetallic nodules photographed in the Pacific Ocean in 2004. Image courtesy of Nodules polym�talliques observ�s lors de la campagne Nodinaut via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 4.0).

Polymetallic nodules photographed in the Pacific Ocean in 2004. Image courtesy of Nodules polym�talliques observ�s lors de la campagne Nodinaut via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 4.0). While many companies may be eager to capitalize on the new era of deep-sea mining sparked by Trumps executive order, TMC was the first company to apply for an exploitation license in international waters via the U.S. It is also forging relationships with partners such as Korea Zinc, which TMC says could pave the way for processing and refining deep-sea minerals on U.S. soil. And, of course, TMC continues to dominate headlines and media coverage in the space.

While the Trump administration has framed deep-sea mining as a core national security and economic interest, some experts warn that TMCs actions to bolster U.S. national security could ultimately create more problems than they solve.

Sally Yozell, a former official with the State Department and NOAA, and current adviser to the environmental security program at the Stimson Center, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank, told Mongabay that the U.S. government and TMC risked creating a literal race to the bottom to access sea minerals. This, she said, could have consequences for the marine environment and also intensify competition between the U.S. and China two countries that already compete with each other in trade and militarily.

Youre going to end up with this kind of Wild West competition between China and the U.S., said Yozell, and who knows where itll go eventually.

Deep-sea mining proponents, on the other hand, are emphasizing the growing mineral competition between the U.S. and China. For instance, on the day Trump released his executive order on deep-sea mining, Rubio posted on X that the United States not China will lead the world in responsibly unlocking seabed mineral resources and securing critical mineral supply chains with our partners and allies.

Hemphill of Greenpeace said he believes the Trump administrations endorsement of the deep-sea mining industry could pave the way for potential legal challenges to its activities. Since many experts view the U.S. move as threatening international law, he also warned it could weaken the United States ability to hold other nations accountable on issues such as illegal fishing, military navigation, and even its own extended continental shelf claims which countries like Russia and Canada contest. The U.S., on the other hand, has stated that it does not believe it is breaking any international laws.

This was a short-term win for them, Hemphill said in reference to TMC. But a great detriment to the United States because this is a huge national security risk that Trump has unleashed.

Elizabeth Claire Alberts is a senior staff writer for Mongabay and a fellow with the Pulitzer Centers Ocean Reporting Network. Find her on Bluesky and LinkedIn .

Additional reporting from Kara Fox, a senior reporter at CNN International.

Banner image by Emilie Languedoc/Mongabay.